A shade over twelve months ago, I had the most consequential encounter of my life. As far as I can tell, that encounter is one that is unique – one that I share with no other soul, living or otherwise.

Let me set the scene for you.

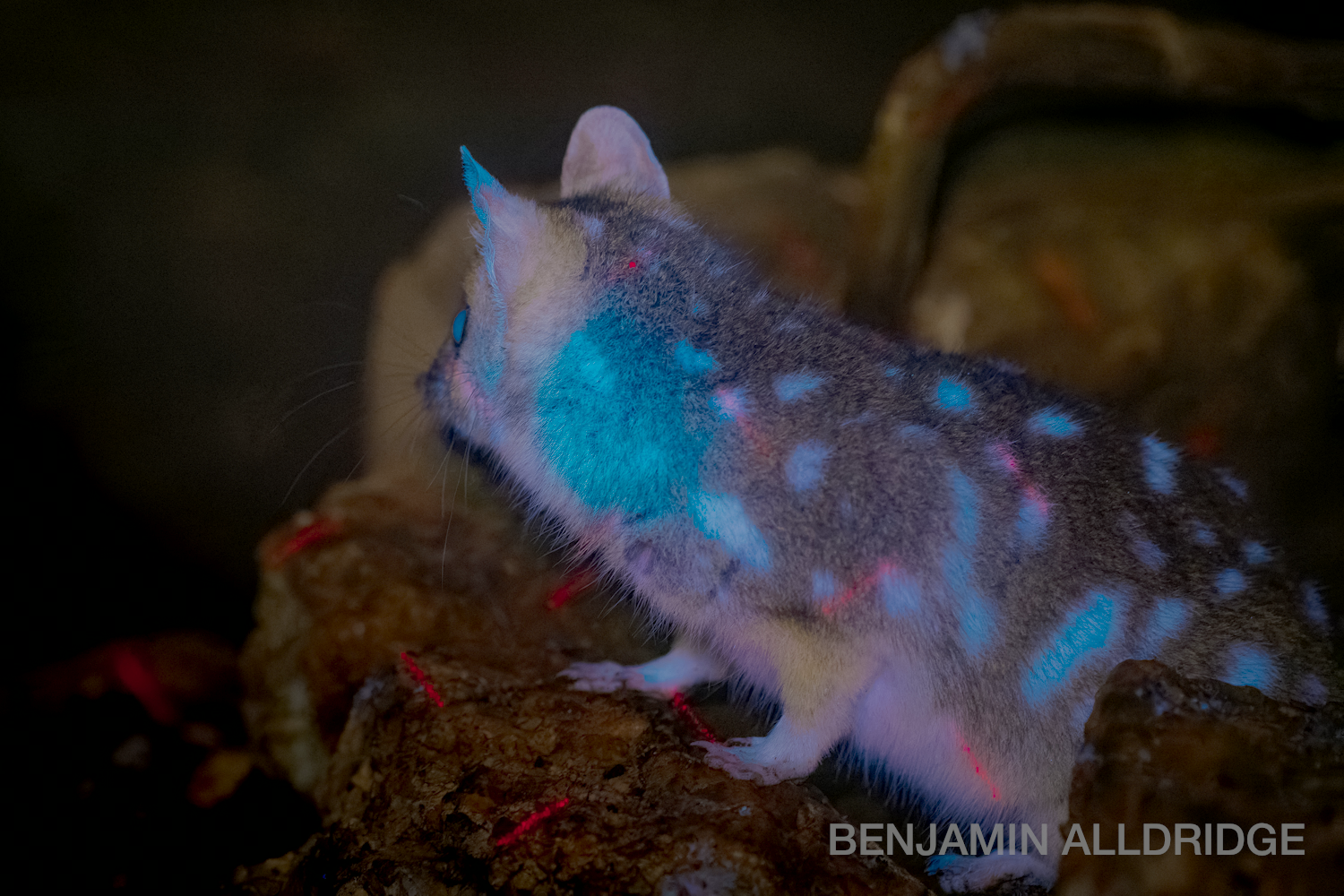

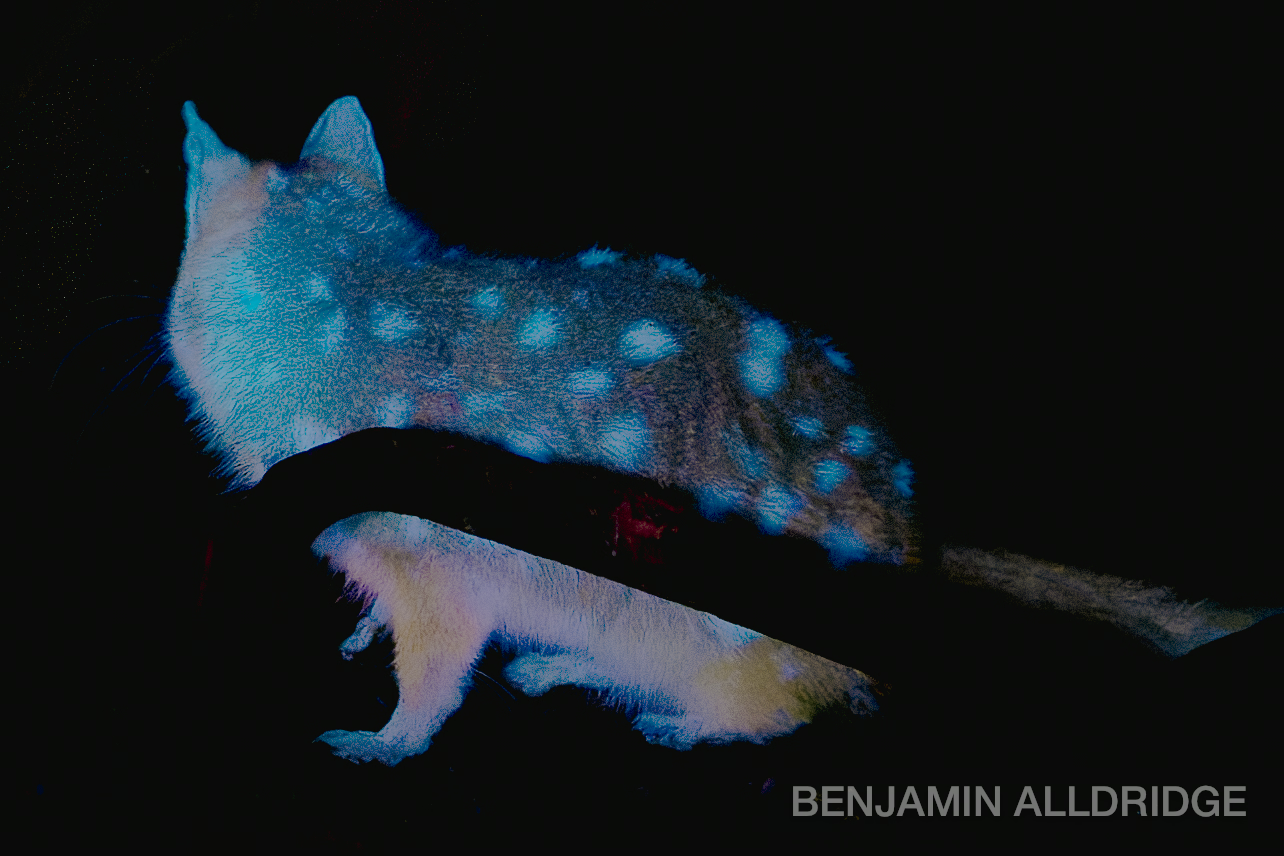

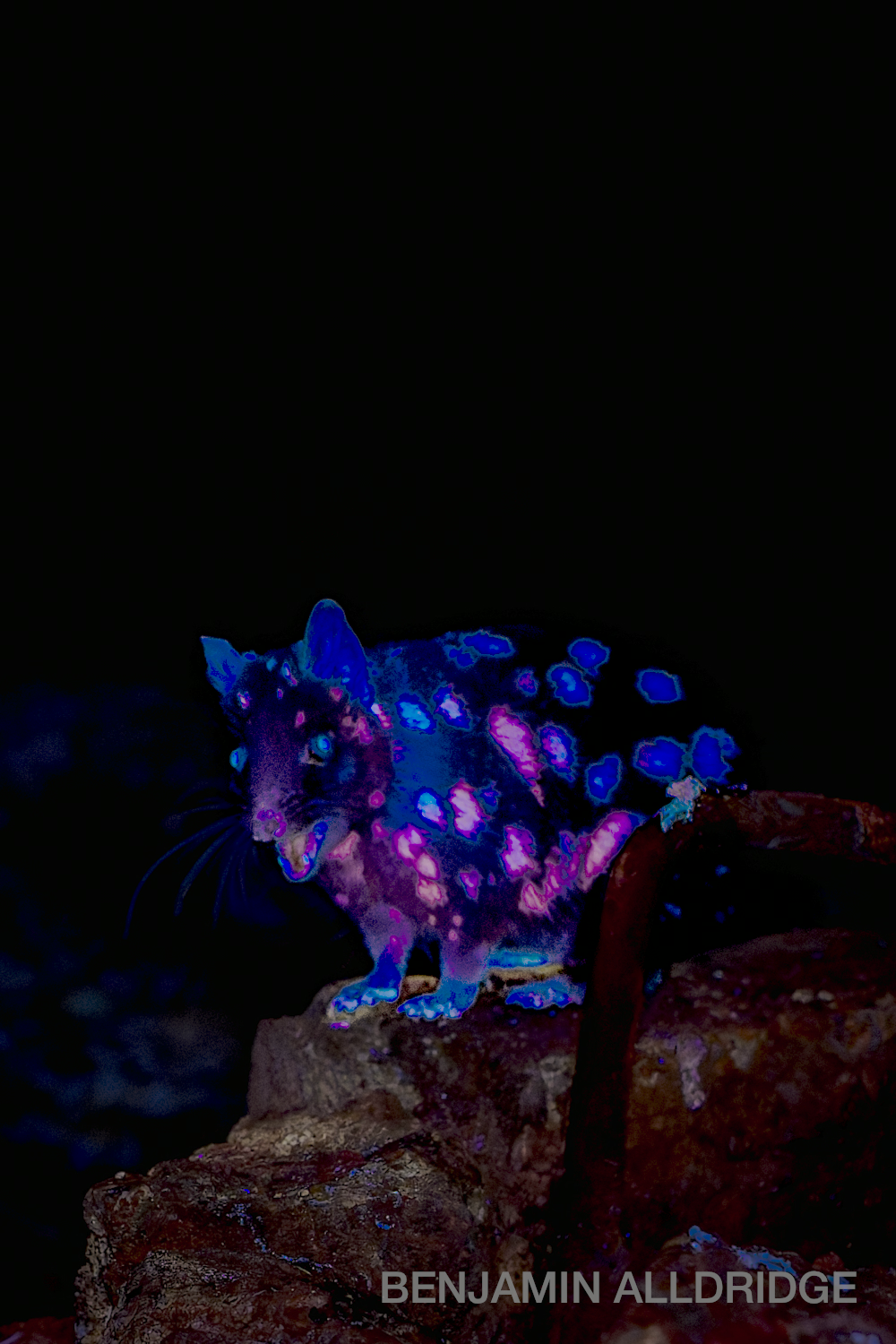

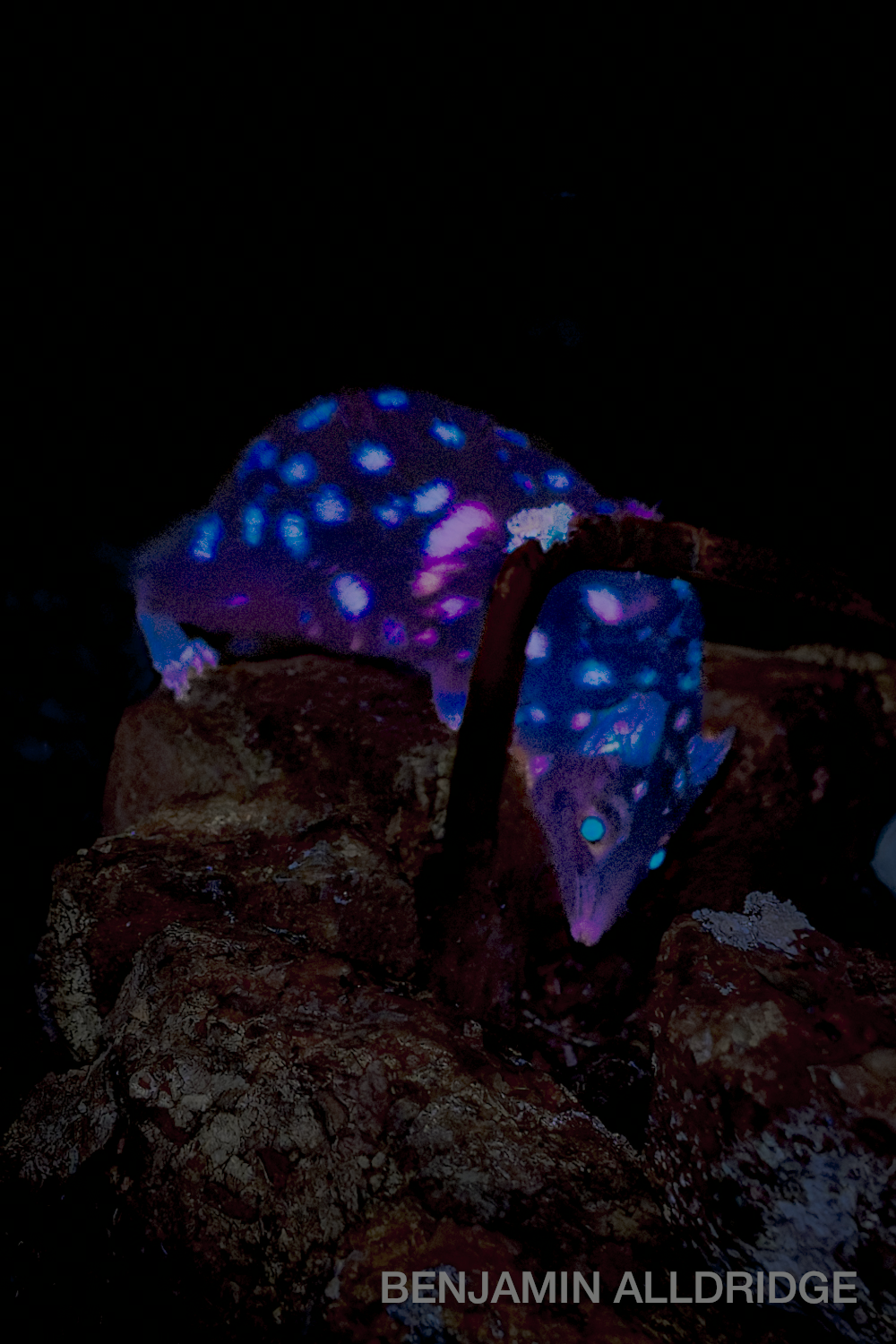

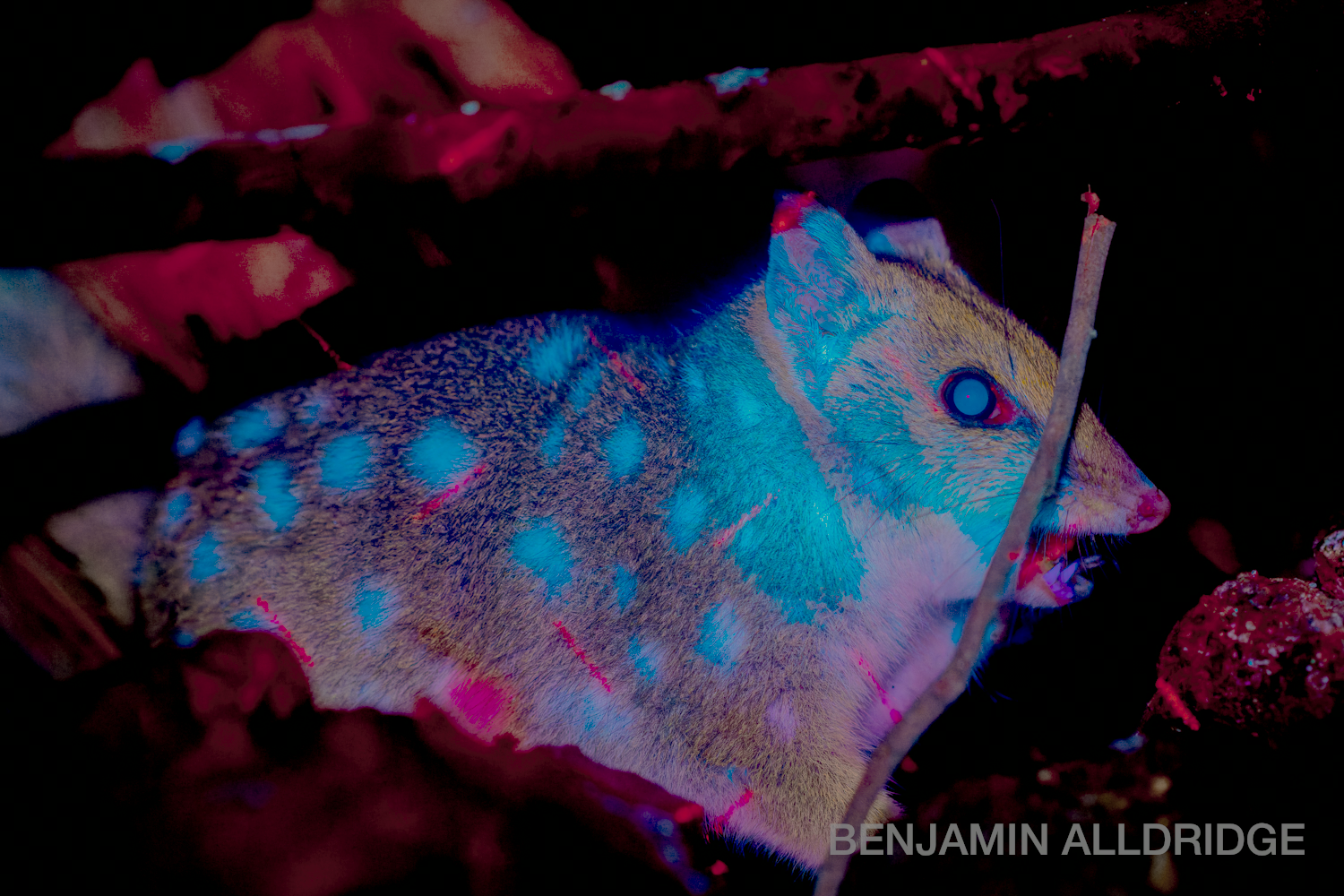

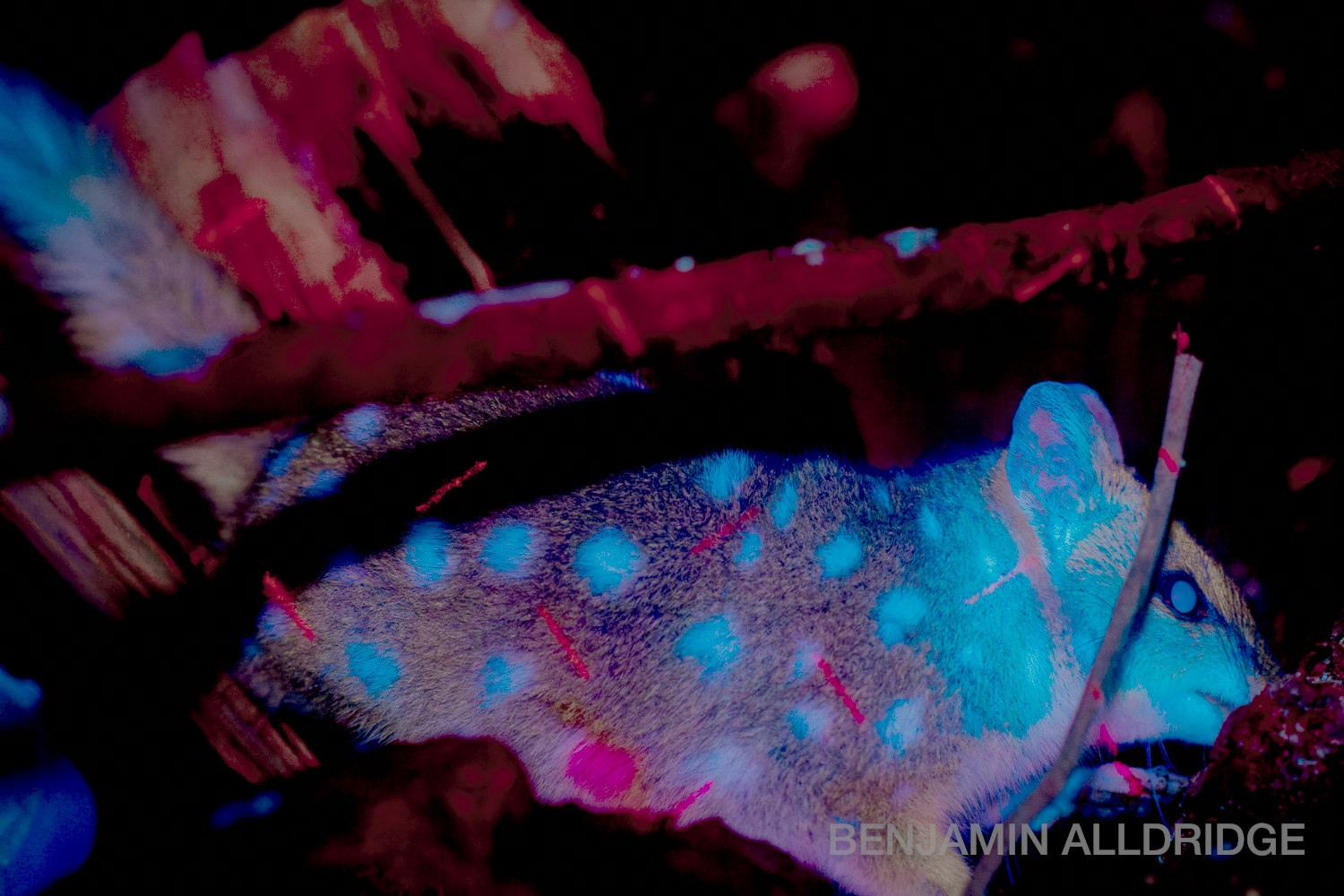

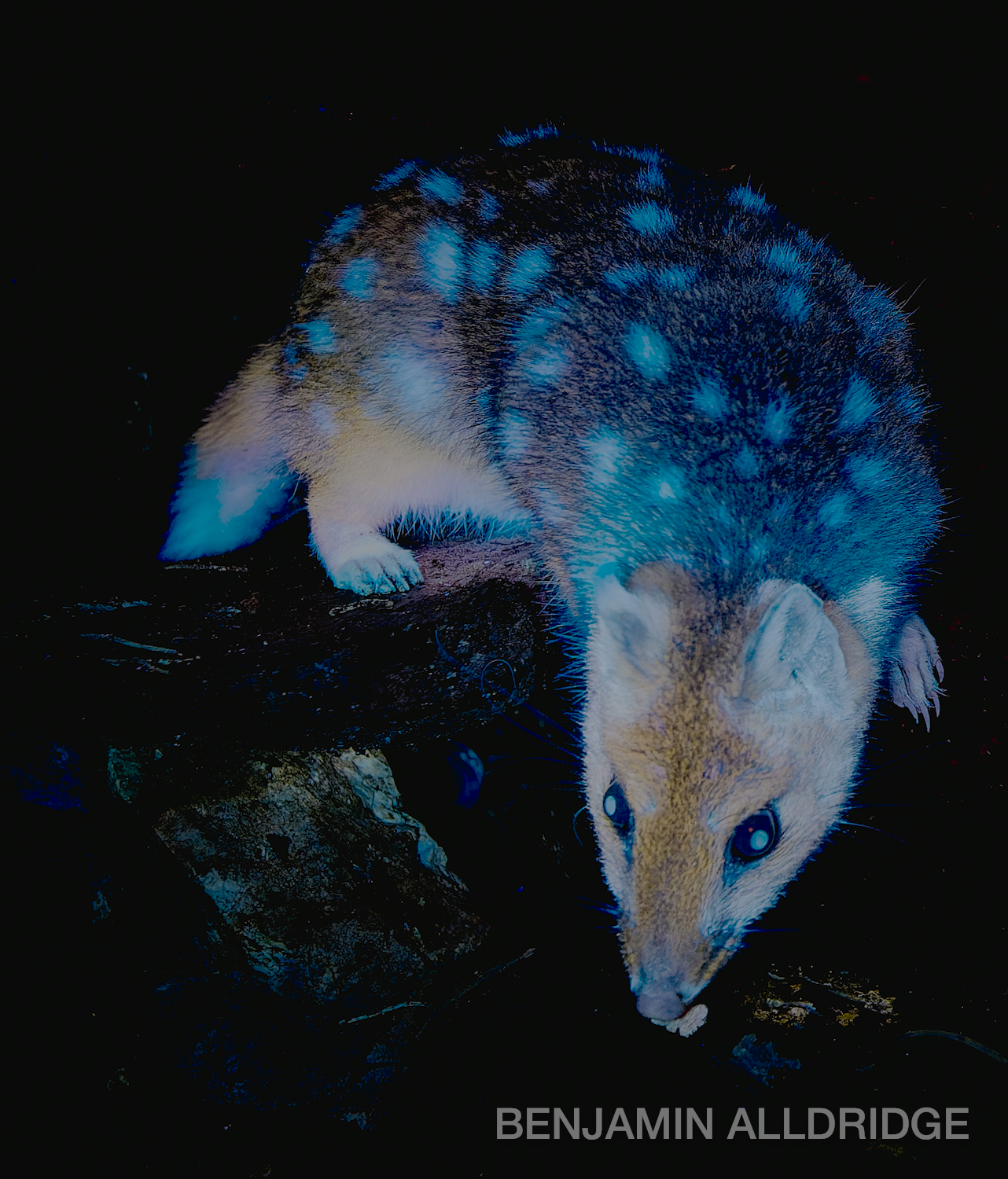

This is the first verifiable documentation of Tasmania’s Eastern quoll (Dasyurus viverrinus, Shaw, 1800), a small Dasyurid exhibiting biofluorescence in the wild, and features both acknowledged colour morphs with a potential pair of novel, intermediate colour morphs. It is also likely amongst the first imagery captured of any of Dasyurid outright in the same contexts.

Back in 2022, I had possibly the other most consequential encounter of my life. To cut a lot of very traumatic preamble out of the fold (which, a topic I’ve already covered, is only relevant as context for why), I found myself in the South West Wilderness area of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area (TWWHA), alone, cold, and sort of miserable reflecting on what lead me to that experience and how I was going to rebuild my existence after being taken to the edge. Reflecting on life; or at least, what cinders remained of it.

I’d just fallen into a bit of a tailspin in my personal life, and it called me to retreat to my “Heart Place” – the place I go to reset. Tasmania’s staggering Southwest is many things, and one of the most beautiful of them is the sense of remoteness while you’re there. It’s just you, the clouds rolling in off of Antarctica’s northern edge, and whatever beasties the bush has in store while you’re there. Occasionally it’s other campers as they ferry to and from the start of the Port Davey track, the gateway to Australia’s most southerly walks; usually it’s the ‘usual suspects’ – wallabies, possums, and the occasional potteroo – and all manner of birdlife like currawongs and wrens. It’s a state of solitude that delivers very suddenly when it does.

For me? A family of Eastern quolls (Dasyurus viverrinus) proved just that – in all at least six of them; 4 fawn and 2 black with possibly another pair of intermediate polymorphs – rummaging through the drizzle-extinguished fire-pit that my dinner had fallen into a few hours earlier. I wouldn’t have really noticed them if not for the sound of rummaging in the pit and scratching on the charcoaled firewood. Their approach is one of pure stealth, which is in such stark contrast to what I’d witnessed by the end of the night.

At first they were timid. Inching closer to the firepit over the course of minutes, in perfect silence. They’d sneak up, take a sniff around for a second or two, and then dart away into the fringing scrub. Gradually though, instants turned into seconds and eventually into minutes. Over the course of four hours, these amazing little cuties hung out with me and came ever-more brazen with their approach over time – culminating with one specimen climbing across my leg as its very own jungle-gym. There was very little aversion once they’d acclimated.

Working on a lifelong project exploring the world of biofluorescence and how it relates to a changing world, I happened to have my (very specialised) lighting kit with me. I hadn’t set out to have this intrusion, but in the moment, opportunity does not wait. The quolls certainly don’t; their frenetic nature if they startle doesn’t lend itself to procrastination.

I’d previously worked with the species in a captive setting at Bonorong Wildlife Sanctuary in the island’s south on a private night visit, but never in the wild. In fact, that’s the hook here – nobody had. As far as I can tell, these are still a year later the only shots in existence of genuine, bona-fide quoll glow in the wild in an unsolicited encounter.

With any luck, you’re looking at this on a HDR display , in which case these images should display the full range of colours actually in them. On older devices, they will fall back to a much muddier representation which has been one of the greatest difficulties with this project. If you aren’t looking at these shots on a good screen, I beg of you, please go and find the closest iPhone or throw it up on your TV!

The fact I managed a tickle over 200 shots in this series between 2 cameras, fully manually focused on each, in pitch black is still astounding to me. The keeper rate is getting on for like 80% – not bad for aiming at a target you can’t guarantee was even there in the first place by the time you fire the shutter. Sitting in silence, framing, focusing, and waiting, operating complex lights, in the bitter Tasmanian winter drizzle, and yet somehow totally captivated in the experience. The fascination these creatures seemed to display for what I was doing is a bond I’m unlikely to forget.

To try to share a bit of how genuinely special this interaction was, these images are edited to be as close to ‘real’ as possible. That has taken months of research to figure how best to process them, and involved meticulous colour correction to reverse the effects of backscatter and the limitations of the basic camera hardware it was captured on. I considered removing the hash marks from the camera focusing, but I think they demonstrate a tangible relationship to reality and just how vivid the colours the animals are showing are.

With the exception of the images captured with white (diffuse 5600 K LED) or blended spectrum (UV/5600 K) illumination, and those witness marks, these images contain no visible light of human origin; that is, everything – all of the light and colour that is captured in each image – is the pure fluorescence of the subjects and the environment around them.

This is continuation of work I started in the early 2010s working with corals and giant clams investigating how fluorescence could be used for tracing health metrics and how mild UV could be used to improve vitality. This project has gone on to now being undertaken at the cutting edge of the field at global scale across a huge range of species across all phyla, with multiple high profile international partners and a wealth of novel discoveries already on the scoresheet.

It is however incredibly important to stress that wildlife are incredibly sensitive to UV and higher energy light sources which is especially true for high output UV torches/flashlights. Interactions should only ever be undertaken with extreme caution and following Leave No Trace principles and DarkSky’s Principles for Responsible Astrophotography. You will not achieve these types of results with standard equipment and without specialist techniques that have taken more than a decade to develop, and attempting to do so is at significant detriment to the subjects.

I’ll be documenting this research as it expands with a view to publication of my observations of specific adaptations, but for now I leave you with the gallery: minimally processed, delivered in (hopefully) HDR and full colour, and just a little bit fun. This night changed my life irrevocably, and so much for the better. We should all be so lucky.

Cameras: SONY ILCE-7M3, Canon EOS 5D Mark IV

Lenses: SIGMA ART 24mm f/1.4, Canon EF 100mm f/2.8 Macro

Illumination: UV-modified flash